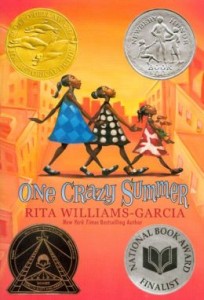

You can hardly see the cover of One Crazy Summer

You can hardly see the cover of One Crazy Summer because of all of the award emblems on it—Scott O’Dell Award for Historical Fiction, Coretta Scott King Award, Newbery Honor, and National Book Award Finalist, with a list of more awards on the back. The story is set in 1968. Delphine, our narrator who is eleven going on twelve, travels across the country with her two younger sisters, Vonetta and Fern, to spend the summer in Oakland, California, with Cecile, the mother Delphine barely remembers.

Delphine struggles to come to terms with the mother who willingly left them and didn’t want them to visit. Cecile wants to be left alone to work on her poetry and every weekday she sends the girls to a Black Panther summer camp where they’re fed meals and taught about black power. Although Delphine has heard terrible things about the Black Panthers from her grandmother, she learns that they’re not all violent terrorists. They’re complex people in a complicated situation, fighting against very real injustices.

Overall it’s an amusing slice-of-life type story (when I described it to my daughter, she asked if it was like The Penderwicks, and in some ways that’s a really good comparison, but with a lot more historical and social consciousness built in). It’s thought provoking without resorting to shocking violence or death. Nothing horribly dramatic happens, but it’s a very formative summer for Delphine who grows up a lot by having a lot of her assumptions quietly challenged. She learns to stand up for herself and make her own decisions.

SPOILER ALERT: Things you might want to know before suggesting this to your kid

Racism

Racism is a pervasive theme through the book, but in a complex way.

The girls’ grandmother, Big Ma, reminds them not to draw attention to themselves, becoming a big “Negro spectacle” and an embarrassment to the whole Negro race. This includes things like the younger girls acting their age—they have to be perfectly behaved because otherwise it brings judgment down on all blacks. This is quite a lot of weight for Delphine to carry, as it’s up to her to make sure her sisters act perfectly.

When they first arrive at the Black Panther center, one of the young men tries hard to get them to call themselves “black” instead of “Negro” and makes a very big deal about it. Fern carries a baby doll everywhere. The doll is white, and that’s one of the reasons she gets mercilessly teased about it. Vonetta takes a black pen to the doll, trying to blacken its skin, ruining the doll completely in the process. In many ways, the girls are reminded that they aren’t black enough and should act differently.

There are many instances of overt racism discussed, though we see few firsthand. Delphine remembers a white policeman pulling over her father and giving him a hard time. He was quiet and respectful despite how horrible the policeman was. Delphine is struck by how little this affects her father—it’s obviously what he’s come to expect. A young unarmed black man was viciously shot while trying to surrender to police. The Black Panthers are rallying to get a park named after him. The father of one of the boys is in prison because he’s an activist. Cecile is arrested because she was in the presence of activists, even though her role in the movement is relatively small. The policemen demolish her kitchen where she prints her poems and some flyers. It seems obvious that this destruction was unnecessary.

Several times tourists want to take pictures of the three cute black girls as if they’re some kind of tourist attraction. These people aren’t mean-spirited, but it doesn’t seem to occur to them that they’re treating people like animals at the zoo. Delphine also realizes that a shopkeeper views them as thieves, even though they came to the store with money hoping to buy souvenirs. They take their business elsewhere. The girls spend a fun day out on their own in San Francisco, but Delphine realizes that she’s much more comfortable in poor, black Oakland, where she doesn’t stand out so much.

Delphine was taught that policemen are supposed to protect and help you. She’s learning secondhand just how much that often isn’t the case if you’re black.

It’s also interesting to see people of other races through Delphine’s eyes. Hirohito is half Japanese, and Delphine has to overcome some of her assumptions about him. “Mean Lady Ming” who runs the nearby Chinese restaurant starts out as foreign and scary, but is less threatening as the girls get to know her. Tourists from another country (maybe Sweden?) seem almost alien with their very blond hair and “flugal, shlugal words.”

Family

Cecile abandoned the girls a few days after Fern was born, leaving them to be raised by their father and grandmother. She will never be the kind of mother that the girls want, and it takes them a while to even think of her as their mother. Over time, eventually they get to know each other a bit, but there’s no miraculous coming together where all the problems go away. However, a line in passing suggests that at least Delphine and Cecile keep in touch after this crazy summer. She finally tells Delphine the story of her very difficult life which helps Delphine understand her now.

The people at the Black Panther center call each other “Brother” and “Sister” which bothers Delphine at first. But eventually Delphine sees that in many ways they are family for each other, especially in how they take care of the girls after Cecile is arrested.

Pa has always done his best for his daughters, even forcing them on the mother who abandoned them. Big Ma loves them, but she’s tough on them. Delphine has had to step up to take care of her sisters, and she’s mature well beyond her years. She sees her sisters as her responsibility, which she takes very seriously. The sisters can be very cruel to each other, but they almost always unite when someone else is mean to one of them. It’s a sweet and realistic portrayal of siblings.

Sexism

Delphine has repeatedly clearly been told that boys can be policemen, firemen, the mayor. Girls will grow up to be teachers or nurses, wives and mothers.

Boys and Sex

All the girls seem to have a crush on Hirohito, and many of them are very silly about it. Delphine eventually becomes friends with him, and he convinces her to ride his go-kart, which is perhaps the most child-like thing she’s done in ages.

Cecile talks about how hard it is to be a young woman on the streets—it doesn’t take much to read between the lines and assume she had some rough times. Eventually Delphine’s father gives her a home, although it’s never mentioned that they got married. Delphine was born the following year. It’s not a very conventional relationship, although it’s been clear that Pa loved her in his way.

Recommendation

There’s a lot in this fairly short book. Delphine is a wonderful narrator, often funny and insightful, always observant. It’s informative and will probably provoke lots of questions about how realistic it is. It’s a great place to start conversations about racism in its many forms. It’s suitable for precocious nine year olds and up, probably ideal for 11 and 12 year olds. Although all of the main characters are female, it should also be of interest to boys. The social and family issues aren’t gender specific.

Daughter Update:

My daughter (13 years old) really enjoyed it and read it quickly, although she was worried that something horrible and tragic was going to happen, despite my assurances that nothing did. But so many books like this rely on tragedy to drive home their point. It’s wonderfully refreshing that this book doesn’t do that.

One Crazy Summer by Rita Williams-Garcia

Published in 2010 by Amistad

Borrowed from Booksfree

Can you give the specific example from the text where you believe Delphine encounters this sexism?

It’s been a while since I read the book, but it was something she was told, I think by an adult – possibly at the same school at home that said the police would protect and help people?